Musings » Encyclopedia of Hydrangeas

Portland, Oregon -- Cambridge, UK

Timber Press 2004

Hiding modestly behind initials, “D.M.” (Dick) is the father and “C.J.” (Cornelius) is the son in this duo. I say modestly because they run an outstanding nursery in the Dutch horticultural headquarters of Boskoop and have been awarded numerous prizes and medals. The Royal Horticultural Society of London gave Dick its Veitch Medal, seldom awarded to anyone who is not British. They are specialists in woody plants and have written extensively about the maple, rhododendrons and conifers.

Many of us have struggled with hydrangeas, not necessarily on the winning side. They are supposed to have blue flowers but the inflorescence remains obstinately pink. The leaves shrivel and die, exposing very “leggy” stems for much of the year. It is hard. In a genus with perhaps a thousand cultivars and varieties, the nurseries carry half a dozen at best. Taxonomic systems vary but there are a least 23 species and 7 subspecies.

Hydrangea is one of those genera which appeared simultaneously in parts of the Americas and East Asia, most particularly China and Japan. It is not found at the Equator or nor is it native to Europe. Asa Gray’s hypothesis of an ancient unitary continent which split in early geological time is used to explain these findings. The most well known species is H. macrophylla often known as “hortensia”. Most of the popular cultivars widely grown at present are derived from this species.

Hydrangeas with white flowers, H. arborescens, were the first to be sent from North America to London in 1736. In spite of its name this shrub never grows more than about 4 feet tall. The other American species are H. sargentiana, H. quercifolia and H. petiolaris. Their supremacy in European gardens declined once the Japanese “hortensias” began appearing in 1823.

An important figure in this transmittal was the larger than life German ophthalmologist Phillip Franz von Siebold. He went to Japan in 1823 and again in 1859. as physician to the Dutch East India Company. The DEIC’s business was confined to the tiny island of Dashima. Before 1854, Japan was closed to Europeans.

Rules meant nothing to Dr von Siebold and he managed to explore the mainland, obtain totally forbidden maps and collect many specimens of native plants, essentially thumbing his nose at the Japanese authorities. He was able to do this because he was an adept surgeon for that period and had many grateful patients.

The authorities did eventually catch up with him and instructed his employers never to send him back again. As he was frantically packing to meet the deadline, one of his local friends gave him a superb hydrangea, H. macrophylla. Once back in Holland, he opened a very elegant nursery and started to write the classic Flora Japonica which inspired Asa Gray.

The Chinese and Japanese hydrangeas are not identical and nomenclature has been exceedingly convoluted. Linnaeus coined the term “hydrangea” combining the Greek words for water (hydra) and vase (angeion). The authors use the late Elizabeth McClintock’s 1957 classification as their guide.

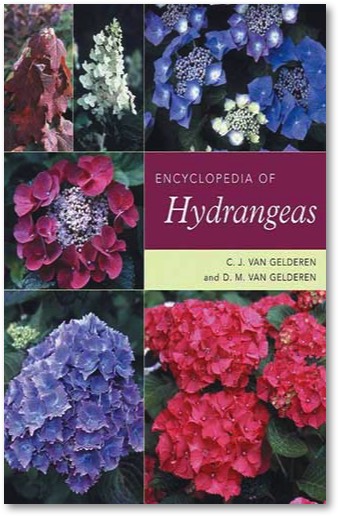

The van Gelderens include more than 800 photographs of this tremendously varied plant, carefully taken in neutral light so as to give a realistic idea of the color. These pictures were almost all taken in Europe. Each photograph has a caption of varying length, giving some of the history, a description of the principal characteristics of the plant in question and brief cultural advice. Their encyclopedic approach brings back many unjustly neglected forms but does not shrink from saying what was wrong with some of them or why they do not deserve to be restored. Some photographs show only the richly hued foliage, a feature we tend to forget.