Press » Samuel Reynolds Hole, Dean of Rochester and Founder of the National Rose Show

It is not given to many respectable churchmen to see themselves described as ”very large, double, resplendent in carmine -pink, with silvery shading and salmon yellow highlights” in their life time but the Very Reverend Dean Hole was the apotheosis of an active Victorian rosarian and had been immortalized in a new hybrid tea rose by Alexander Dickson, a leading Northern Irish rose grower of the period. There are still Dicksons growing roses today. The dean reveled in the fun.

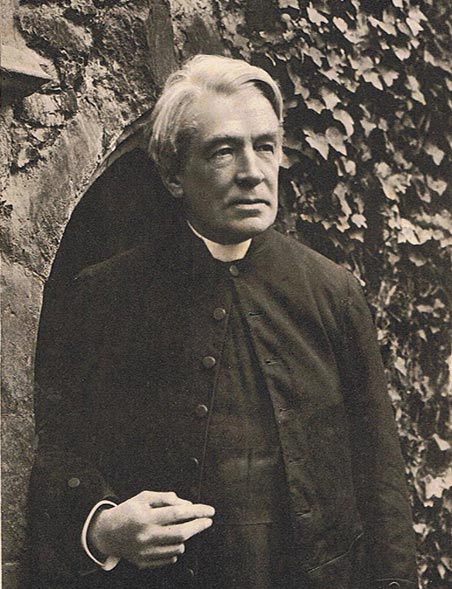

Dean Hole

Roses inspire a completely irrational passion in the least likely of bosoms, akin only to that caused by orchids. Trying to understand it involves a tiny bit of garden history. Modern gardens evolved from tiny patches of lawn with a few flowers around them safely enclosed behind the high walls of a Mediaeval castle keep to faux tapestry parterres, great natural seeming parks, huge shrubberies and serried masses of annual flowers by the Victorian era.

Those initial gardeners used whatever plants were at hand. The native British flora was beginning to be augmented by new plants from the continent. England had its own red and white native roses which only bloomed once a year. The Normans brought wallflowers and carnations with them as weeds attached to the stone for building castles. The Crusaders later brought anemones from their travels.

What ignited the singular obsessions for a particular plant was the arrival of huge numbers of newly discovered plants from North and South America, China, Japan, South Africa, India, India, Indonesia and the Antipodes during the nineteenth century. They were gorgeous, exotic and came in many different colours and varieties. For the first time there was extraordinary choice within the same sort of flower.

The roses from China which were not only beautiful but bloomed at least twice a year gave rise to a new frenzy. I have referred elsewhere to the ”What If” brigade, imaginative plant growers who saw wonderful new flowers emerging from combining two different kinds. Once the religious prohibition on deliberate cross breeding dwindled away in the early 1830s, the race was on. The first repeating Chinese rose was a delicate pink, small and modest but what if it could have larger and more striking blossoms. It is perhaps a bit surprising that clergymen were quite often in the forefront of this movement, clergymen and station masters.

Samuel Reynolds Hole, 1819 – 1904, was born on December 5, 1819 in Caunton, Nottinghamshire. He outlived Queen Victoria by three years. While still a very young man he made a note in his diary that “his eye had rested on a rose”. That seemed to be a simple casual comment but the next day he returned to that garden with paper and pencil as well as a small book about roses by William Rivers. The Duke of Devonshire underwent a similar epiphany with an oncidium orchid. It captured his soul. Reynolds Hole’s index rose was Rosa gallica ‘d’Aguesseau’.

Those initial gardeners used whatever plants were at hand. The native British flora was beginning to be augmented by new plants from the continent. England had its own red and white native roses which only bloomed once a year. The Normans brought wallflowers and carnations with them as weeds attached to the stone for building castles. The Crusaders later brought anemones from their travels.

What ignited the singular obsessions for a particular plant was the arrival of huge numbers of newly discovered plants from North and South America, China, Japan, South Africa, India, India, Indonesia and the Antipodes during the nineteenth century. They were gorgeous, exotic and came in many different colours and varieties. For the first time there was extraordinary choice within the same sort of flower.

The roses from China which were not only beautiful but bloomed at least twice a year gave rise to a new frenzy. I have referred elsewhere to the ”What If” brigade, imaginative plant growers who saw wonderful new flowers emerging from combining two different kinds. Once the religious prohibition on deliberate cross breeding dwindled away in the early 1830s, the race was on. The first repeating Chinese rose was a delicate pink, small and modest but what if it could have larger and more striking blossoms. It is perhaps a bit surprising that clergymen were quite often in the forefront of this movement, clergymen and station masters.

Samuel Reynolds Hole, 1819 – 1904, was born on December 5, 1819 in Caunton, Nottinghamshire. He outlived Queen Victoria by three years. While still a very young man he made a note in his diary that “his eye had rested on a rose”. That seemed to be a simple casual comment but the next day he returned to that garden with paper and pencil as well as a small book about roses by William Rivers. The Duke of Devonshire underwent a similar epiphany with an oncidium orchid. It captured his soul. Reynolds Hole’s index rose was Rosa gallica ‘d’Aguesseau’.

Rosa gallica ‘d’Aguesseau’

After taking holy orders Hole became the vicar of Caunton in 1850. In 1887 he was elevated to dean of Rochester Cathedral. Everyone who met him remembered his warmth, largeness of spirit and genuine concern for all who suffered. He took his pastoral work very seriously and nothing stood in its way. The plight of the children who slaved away in monstrous factories for pennies a week really distressed him and he, together with Mrs Gaskell, worked very hard to improve their lot.

Rochester Cathedral

This warmth and caring were also clearly seen within his family. His wife and children doted on him. Lord David Cecil once said “If you want to know about a man’s talents, you should see him in society. If you want to know about his temper you should see him at home”.

All this is by way of saying he had his priorities correct but now back to the roses. At that period rose fanciers were like islands in an archipelago until Dean Hole came up with the idea of a national society where they could get together and compare notes. The example of the London Horticultural Society, later to become the Royal Horticultural Society in 1861 by edict of Prince Albert, lay before him. There was a National Carnation and Picotee Society too. The National Rose Show began in 1876.

All this is by way of saying he had his priorities correct but now back to the roses. At that period rose fanciers were like islands in an archipelago until Dean Hole came up with the idea of a national society where they could get together and compare notes. The example of the London Horticultural Society, later to become the Royal Horticultural Society in 1861 by edict of Prince Albert, lay before him. There was a National Carnation and Picotee Society too. The National Rose Show began in 1876.

Deans wore 'Shovel' hats

The show held meets during the year. This was very serious business. There were cups and awards to be won. Placement on the show benches was very important. The founders set very high standards and rigid rules about how it would proceed. It was not unknown for a staid clergyman to have a tantrum out of frustration with these rules in the most indecorous way.

Consider the Reverend Joseph Pemberton, normally a very mild mannered man who lived with his sister Florence in Havering-atte-Bower, Essex. Joseph had joined the new society in 1877 and his sister a year later in 1878. They worked as a team. The rose malaise had seized him while he was still a schoolboy. He and Florence spent all their spare time in their three acre garden reaching for perfection in their roses.

He had won other competitions so was feeling very confident when he entered the 1877 National Rose Show. There was some sort of mishap and his entry arrived the day after the closing date for submissions. Previously he had found that other club officials were very flexible about such matters but the NRS said no.

Pemberton went to expostulate in person and was shown other equally gorgeous entries which had been rejected. That made no impression on him. He simply took his roses from space to space around the hall until the Reverend D’Ombrain, club secretary, threw up his hands and allowed him to remain.

The love of roses led to unusual camaraderie across the social classes. Earls and dukes would chat easily with middle or even working class men over how to grow a better rose. The head gardener of a great estate was an absolute ruler in his domain, telling his employer quite candidly when he was wrong and the employer meekly accepting the rebuke. This led Dean Hole into close acquaintance with many aristocrats who would not otherwise have paid any attention to a rural vicar or even the dean of a cathedral.

The Duke of Rutland had told him to visit his gardens at Belvoir Castle whenever he was in Leicestershire. When the dean got there the head gardener realized that this was no ordinary tourist but someone who understood roses. He asked to whom he had the pleasure of speaking. As the dean told him his name the gardener turned round to his underlings and shouted “Turn on the fountains”! It was a sure sign of his esteem.

Dame Sybil Thorndike, the very well known English actress, grew up in Rochester and visited the dean as a girl. She is the one who remembered this anecdote.

Consider the Reverend Joseph Pemberton, normally a very mild mannered man who lived with his sister Florence in Havering-atte-Bower, Essex. Joseph had joined the new society in 1877 and his sister a year later in 1878. They worked as a team. The rose malaise had seized him while he was still a schoolboy. He and Florence spent all their spare time in their three acre garden reaching for perfection in their roses.

He had won other competitions so was feeling very confident when he entered the 1877 National Rose Show. There was some sort of mishap and his entry arrived the day after the closing date for submissions. Previously he had found that other club officials were very flexible about such matters but the NRS said no.

Pemberton went to expostulate in person and was shown other equally gorgeous entries which had been rejected. That made no impression on him. He simply took his roses from space to space around the hall until the Reverend D’Ombrain, club secretary, threw up his hands and allowed him to remain.

The love of roses led to unusual camaraderie across the social classes. Earls and dukes would chat easily with middle or even working class men over how to grow a better rose. The head gardener of a great estate was an absolute ruler in his domain, telling his employer quite candidly when he was wrong and the employer meekly accepting the rebuke. This led Dean Hole into close acquaintance with many aristocrats who would not otherwise have paid any attention to a rural vicar or even the dean of a cathedral.

The Duke of Rutland had told him to visit his gardens at Belvoir Castle whenever he was in Leicestershire. When the dean got there the head gardener realized that this was no ordinary tourist but someone who understood roses. He asked to whom he had the pleasure of speaking. As the dean told him his name the gardener turned round to his underlings and shouted “Turn on the fountains”! It was a sure sign of his esteem.

Dame Sybil Thorndike, the very well known English actress, grew up in Rochester and visited the dean as a girl. She is the one who remembered this anecdote.

Belvoir Castle

The dean had been absorbing knowledge about roses from many sources over the years such as other men’s books, his own observations and conversations with experts. In 1869 he published “A Book About Roses”. This work cemented his reputation. When he was just beginning he read books by William Rivers and William Paul. They were true pioneers. The hybridization movement had only got under way in the mid-1830s though some earlier gardeners were crossing flowers subrosa for fear of offending the church. Roses are genetically very flexible. Even one which has several ancestors and might be considered to be sterile can still be used to breed successfully. William Paul’s book appeared in 1848 and went through many editions.

Dean Hole wrote ten other books, including some “memories” in 1892. He remained president of the rose show which later became the National Rose Society and then the Royal National Rose Society for many years. He corresponded with friends and colleagues at length. The move from the vicarage at Caunton to the Deanery at Rochester was a very emotional event. Not least was having to leave his garden behind.

The dean lectured about roses all over the British Isles and made one tour of the United States. Wherever he was he sat down and wrote to his beloved wife Caroline all the time.

Whatever flaws the dean might have had were completely neutralized beneath the fullness of his life and integrity of his spirit. There went a man.

References

Harkness, Jack 1985 “Makers of Heavenly Roses”

London Souvenir Press

Massingham, Betty 1974 “Turn on the Fountains: the life of Dean Hole”

London Gollancz

Quest-Ritson, Charles 2003 “Climbing Roses of the World”

Portland, Oregon London Timber Press

Paul, William 1848 “The Rose Garden”

London Shirwood, Gilbert and Piper

Dean Hole wrote ten other books, including some “memories” in 1892. He remained president of the rose show which later became the National Rose Society and then the Royal National Rose Society for many years. He corresponded with friends and colleagues at length. The move from the vicarage at Caunton to the Deanery at Rochester was a very emotional event. Not least was having to leave his garden behind.

The dean lectured about roses all over the British Isles and made one tour of the United States. Wherever he was he sat down and wrote to his beloved wife Caroline all the time.

Whatever flaws the dean might have had were completely neutralized beneath the fullness of his life and integrity of his spirit. There went a man.

References

Harkness, Jack 1985 “Makers of Heavenly Roses”

London Souvenir Press

Massingham, Betty 1974 “Turn on the Fountains: the life of Dean Hole”

London Gollancz

Quest-Ritson, Charles 2003 “Climbing Roses of the World”

Portland, Oregon London Timber Press

Paul, William 1848 “The Rose Garden”

London Shirwood, Gilbert and Piper

English Historical Fiction Authors, July 16, 2019