Press » Why Green Olives Come in Jars But Black Ones Come in Cans

Part 1: The Quest

This is just one of the stories from our I’ve Always Wondered series, where we tackle all of your questions about the world of business, no matter how big or small. Ever wondered if recycling is ? Or how store brands name brands? What do you wonder? Let us know .

Carol Shearer of , says this started as an economic question in the grocery store. She needed black olives, but not a whole can.

She wondered: Why can’t you get black olives in a jar like you do the other kind?

So, , we went on the hunt…

Getting to the bottom of this question was not easy. We asked three people:

First up: Mort Rosenblum, author of “The Olive: Life and Lore of a Noble Fruit.“

“That’s a wild question,” he said. “Which I don’t think I can answer.”

This is just one of the stories from our I’ve Always Wondered series, where we tackle all of your questions about the world of business, no matter how big or small. Ever wondered if recycling is ? Or how store brands name brands? What do you wonder? Let us know .

Carol Shearer of , says this started as an economic question in the grocery store. She needed black olives, but not a whole can.

She wondered: Why can’t you get black olives in a jar like you do the other kind?

So, , we went on the hunt…

Getting to the bottom of this question was not easy. We asked three people:

First up: Mort Rosenblum, author of “The Olive: Life and Lore of a Noble Fruit.“

“That’s a wild question,” he said. “Which I don’t think I can answer.”

What, and black olives are ugly?

Nope. Actually, they came in glass jars, too, once upon a time. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

Next up, we took our “wild question” to the staff of Eataly, a high-concept Italian food complex that just opened a branch in Chicago.

Dave Malzan is a manager in the Salumi-Formaggi department, which includes the olive bar, with olives from all over Italy.

Malzan said I was in the wrong place.

“If you’re thinking about the olives at your grandma’s house that you may have worn on your fingers on Thanksgiving? No, those guys we do not carry.”

Malzan says Eataly isn’t just about eating. Eataly is about knowing the story of what you’re eating.

Nope. Actually, they came in glass jars, too, once upon a time. But that’s getting ahead of ourselves.

Next up, we took our “wild question” to the staff of Eataly, a high-concept Italian food complex that just opened a branch in Chicago.

Dave Malzan is a manager in the Salumi-Formaggi department, which includes the olive bar, with olives from all over Italy.

Malzan said I was in the wrong place.

“If you’re thinking about the olives at your grandma’s house that you may have worn on your fingers on Thanksgiving? No, those guys we do not carry.”

Malzan says Eataly isn’t just about eating. Eataly is about knowing the story of what you’re eating.

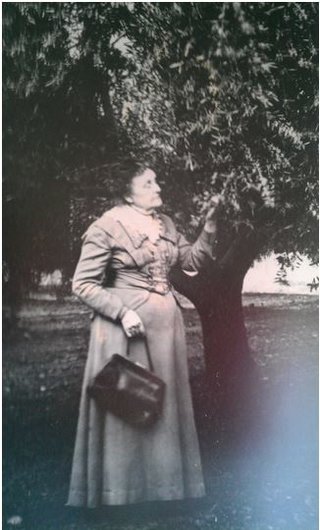

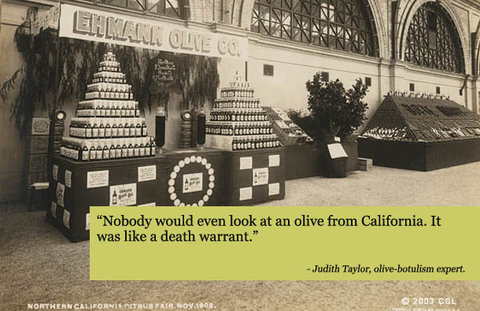

Actually, there’s a great story. And finally, I found the person who knows it best: Judith Taylor, who wrote the other book on olives. She’s a retired physician who now writes horticultural histories. In 2000, she published “The Olive in California: History of an Immigrant Tree“.

Part 2: The Story

The black olive—also known as the California ripe olive—was invented in Oakland, by a German widow named Freda Ehmann.

Part 2: The Story

The black olive—also known as the California ripe olive—was invented in Oakland, by a German widow named Freda Ehmann.

Freda Ehmann

In the mid-1890s all she had was an olive grove nobody thought was worth very much.

“She must have been an amazing and remarkable woman,” Taylor says. “Because instead of sitting in her daughter’s rocking chair in Oakland, she decided to get busy and pick the olives and do something with them.”

She got a recipe from the University of California for artificially ripening olives. (Green olives are pickled green— as in, not ripe.)

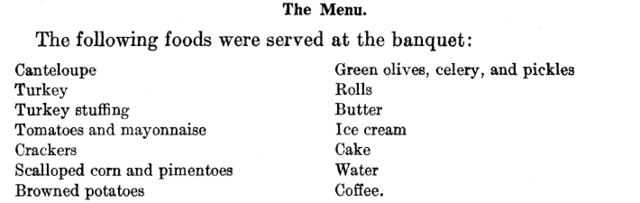

From a 1918 local history:

“She must have been an amazing and remarkable woman,” Taylor says. “Because instead of sitting in her daughter’s rocking chair in Oakland, she decided to get busy and pick the olives and do something with them.”

She got a recipe from the University of California for artificially ripening olives. (Green olives are pickled green— as in, not ripe.)

From a 1918 local history:

“Returning to her daughter’s house in Oakland, she turned the back porch into a pickling plant, got some wine-casks, cut them in two, and went to work. Uncertain of the result, she dared not assume the expense of piping water to the vats, so that through all the process of leaching and pickling she carried the gallons of water herself. Passing restless nights, she went to work at five o’clock in the morning, and all through the day and until late in the evening she watched the slow and mysterious changes of the fruit.”

Freda perfected the recipe, sold her olives locally, then went East to open up new markets. She scored her first hit in Philadelphia.

Eventually, she had a national business, requiring new orchards, and factories. She kept going back to the University of California for more tips—including packaging.

“When she first went to Philadelphia, she had them in kegs and barrels—just sort of loosely covered, you know,” Taylor says. “Not sealed.”

Then, glass jars. Because they don’t spill?

“Yes, and they’re very pretty,” Taylor says. “And gradually they developed a technique of sealing the jars effectively. And with that came trouble.”

You seal the jar, and what’s inside?

“That’s a perfect cultural medium for botulism,” Taylor says.

In 1919, olive-related botulism outbreaks started killing people.

In August, 14 people got sick after a dinner party at a country club near Canton, Ohio. Seven of them died.

A week later, epidemiologists went to work, interviewing the survivors. Pinpointing the olives as the source of those deaths involved some great detective work. Their report includes:

Eventually, she had a national business, requiring new orchards, and factories. She kept going back to the University of California for more tips—including packaging.

“When she first went to Philadelphia, she had them in kegs and barrels—just sort of loosely covered, you know,” Taylor says. “Not sealed.”

Then, glass jars. Because they don’t spill?

“Yes, and they’re very pretty,” Taylor says. “And gradually they developed a technique of sealing the jars effectively. And with that came trouble.”

You seal the jar, and what’s inside?

“That’s a perfect cultural medium for botulism,” Taylor says.

In 1919, olive-related botulism outbreaks started killing people.

In August, 14 people got sick after a dinner party at a country club near Canton, Ohio. Seven of them died.

A week later, epidemiologists went to work, interviewing the survivors. Pinpointing the olives as the source of those deaths involved some great detective work. Their report includes:

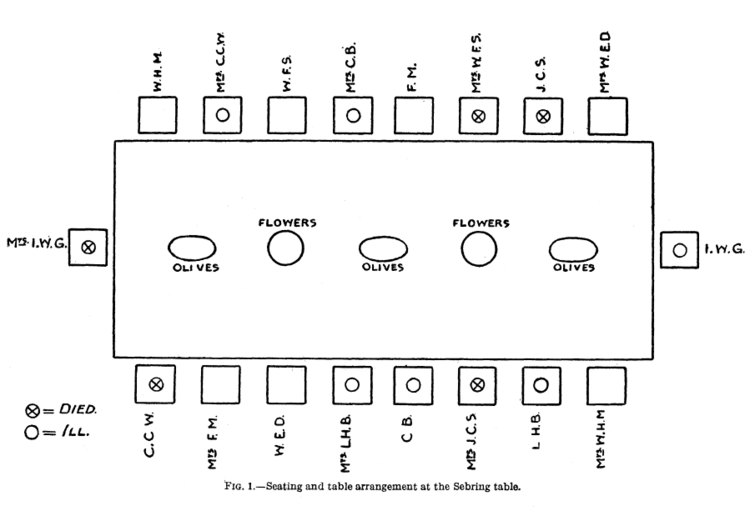

…the seating chart. X marks the spot where people died:

… and a thorough discussion of who ate what, to eliminate other possible causes. For instance:

And the final, damning conclusion:

“The occurrence of poisoning at the Sebring table can be accounted for only by the ripe olives served at this table.”

Among the waiters at the club there is a custom of collecting the delicacies after the diners have finished, and the two waiters poisoned did so collect the left-over olives and ate some of them. Later, waiter C.O. carried the olives to the chef with the request that he “Try one of these damn things, they don’t taste right to me.” The chef ate two and later died.“

Among the waiters at the club there is a custom of collecting the delicacies after the diners have finished, and the two waiters poisoned did so collect the left-over olives and ate some of them. Later, waiter C.O. carried the olives to the chef with the request that he “Try one of these damn things, they don’t taste right to me.” The chef ate two and later died.“

The 1919 case didn’t involve Freda Ehmann’s olives. But a 1924 case did.

The next decade was murder for the California olive industry.

The next decade was murder for the California olive industry.

The whole industry switched to a new standard for the ripe California olive.

“It has to be heated to 240 degrees. And only a can would tolerate that, physically—you couldn’t do that with a glass jar.”

Eventually, California olives came back. In cans.

“It has to be heated to 240 degrees. And only a can would tolerate that, physically—you couldn’t do that with a glass jar.”

Eventually, California olives came back. In cans.

But Ehmann had long since retired. She was heartbroken.

“She couldn’t come to terms with the fact that something she’d done had killed people,” Taylor says.

Today, there are just two olive-canning companies in California.

“She couldn’t come to terms with the fact that something she’d done had killed people,” Taylor says.

Today, there are just two olive-canning companies in California.

Marketplace, June 21, 2017